Interview with the Recipent of the Google PhD Fellowship 2025: Luca Eyring

Aktuelles |

1. Congratulations on receiving the Google PhD Fellowship 2025 in the category “Machine Learning and ML Foundations”. Could you briefly introduce your research topic and share what you're currently working on?

Thank you! My research centers on generative modeling, specifically diffusion models. These are the engines behind Text-to-Image systems like Stable Diffusion, DALL-E, and Midjourney.

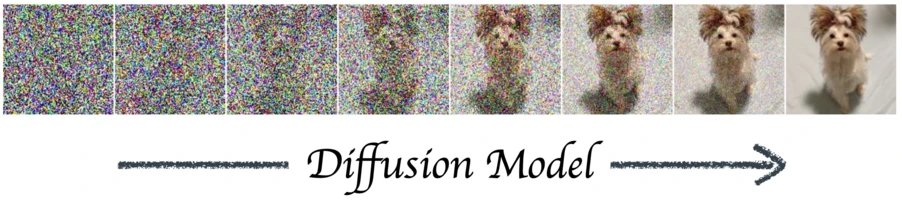

The core idea is simple: a diffusion model learns to denoise. During training, we take real images, gradually corrupt them with random noise, and teach the model to reverse this process. At generation time, we can then sample pure random noise and let the model progressively denoise it into a coherent image.

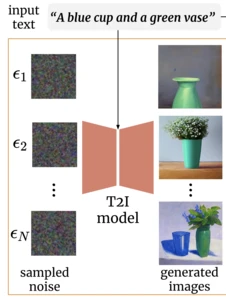

Here's where it gets interesting, and where my research comes in. That initial noise we sample at generation time has a profound effect on the final image we get. Given the same prompt, one noise sample might produce an image that perfectly captures every detail, while another might miss key elements entirely. It's a bit like how shuffling a deck of cards determines the hand you're dealt. Two different shuffles, two different outcomes, even if the rules of the game stay the same.

Traditionally, this noise is treated as just a random variable, something we have no control over. My research challenges this assumption. In my recent work, I showed that we can manipulate this noise at generation time using feedback on the generated image. Rather than hoping we get lucky with our random sample, we can strategically shape the noise to steer generation. This steering is quite flexible, and we can use it to generate, say, more red images, or more importantly, higher-quality outputs that better match the prompt.

More broadly, my doctoral research aims to give users control over this noise, turning it from a hidden source of randomness into something we can understand and steer. If we can learn what different noise patterns do to the final image, we open up new ways for people to guide and trust generative AI.

2. For your doctorate, you are researching both at TUM and at the Helmholtz AI, plus you are a doctoral candidate at ELLIS (the European Laboratory for Learning and Intelligent Systems). How are these three institutions connected to your research?

Impactful research is rarely done alone. I'm fortunate to collaborate with brilliant researchers worldwide, and being part of TUM, Helmholtz AI, and ELLIS has been instrumental in facilitating these collaborations.

Let me start with ELLIS. Every ELLIS doctoral candidate has two supervisors, but I'm part of the industry track, which means my second supervisor is based at a company, in my case, Inceptive. This gave me the opportunity to work on RNA design and apply ideas from my research to problems with direct real-world impact. Having two supervisors with different perspectives has been a great experience, and I'd encourage anyone to seek out that kind of setup.

Our lab, the Explainable Machine Learning group, is located jointly at TUM and Helmholtz AI This enables us to tap into the deep machine learning expertise at TUM while also engaging in interdisciplinary projects through Helmholtz Munich.

Ultimately, these affiliations have shaped not just what I research, but how I research, by surrounding me with diverse perspectives and opening doors to collaborations I wouldn't have found otherwise.

On that note, I would like to thank my two amazing advisors, Zeynep and Alexey, as well as all my collaborators.

3. Could you give us a glimpse into your day-to-day research life and tell us what a typical day looks like for you?

A big part of my day is spent coding and reading papers. Beyond that, there are reading groups, research discussions, and meetings with collaborators. No two days look exactly the same, which is part of what makes it exciting.

One thing that shapes my daily routine is running experiments on a compute cluster. These aren't lab experiments but computational ones, like training a model on millions of images, and they can take hours or even days to complete. I've developed a rhythm around this: I start experiments in the evening and let them run overnight. In the morning, I kick off new ones over a coffee at home, then head to the office and check on everything. This creates natural breaks in my work and keeps things moving even when I'm not actively working.

4. You started your doctorate in August 2023. What has been the most rewarding aspect of your journey so far – and what has been the most challenging?

The most challenging aspect has been learning to say no. As a doctoral candidate, I have a lot of freedom to choose what I work on and whom I work with. That's a privilege, but it also means prioritization becomes critical. You simply cannot pursue every interesting project or collaboration. Learning to focus and protect my time, even when something sounds exciting, has been one of the harder lessons.

Having just returned from NeurIPS, the largest machine learning conference, the most rewarding aspect has undoubtedly been attending conferences. I've been fortunate to attend four major ML conferences now, and they've been incredible experiences. What really stays with me is the people: meeting researchers whose papers I've read, having spontaneous conversations that spark new ideas, and feeling the collective excitement about where the field is heading. Those weeks are the highlights of my PhD.

5. Looking ahead, how do you envision your research evolving over the next few years, especially in light of the rapid developments in machine learning?

Let me return to the Text-to-Image example. When a user generates an image, they specify the prompt, but as we discussed, a significant part of the output is actually determined by the initial noise. Right now, that's a black box to the user.

I envision this changing. My research is moving toward making the noise space not just something we can manipulate, but something we can interpret and control in intuitive ways. While this type of control is relevant for image generation, it is even more crucial for scientific applications, where the right control could lead to the creation of new medicines and materials that wouldn't have been discovered otherwise. As these models become increasingly powerful and expand into new domains, this control will only become more important.